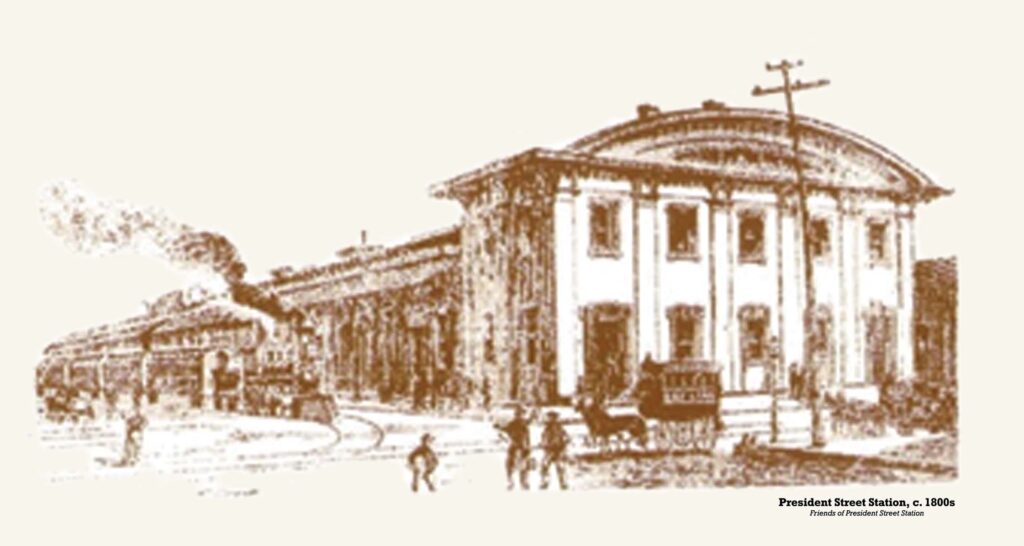

During the waning years of slavery’s presence in Maryland, enslaved individuals continued to fight and reach freedom in the North through the innovations of the railroad systems. On New Year’s Day in 1856, officers arrested a pair of enslaved families braving the winter cold in the hopes of riding both the B&O and the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore railroad systems. The two families hailed from Staunton, Virginia, and Charleston, South Carolina. Officers Peter P. Potee, J. Graham, and Francis T. McKinley foiled their escape for the North, one aimed to go as far as New York.

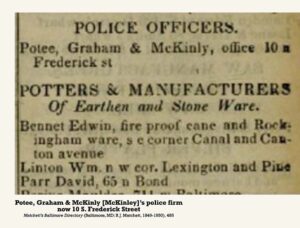

The trio ran an independent police firm in Baltimore, active as early as 1849. Potee, Graham & McKinley were able to ride a police boom in the 1850s with the development of the city’s police department, the support of white vigilantes, and the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

These three policemen apprehended the families at the two train depots and took them to a private jail in the city. These freedom seekers attempted to escape a world of depravity and were tragically introduced to its system designed to retrieve them after capture.

Private slave jails rose to prominence after 1817 when Maryland state law banned slave traders from using public jails. Slave traders typically owned these jails and offered them to slaveholding locals to oversee enslaved individuals when their owners were out of town. They were present throughout downtown Baltimore, and conditions were “abhorrent to every condition of humanity.” Some of the most well-known slave traders and operators in Baltimore throughout the nineteenth century include Joseph Donovan, Austin Woolfolk, and Hope Hull Slatter. By 1845, only enslaved felons went to public prisons, such as the city jail. Those charged with lesser crimes, such as attempts to flee, were sent to these private jails.

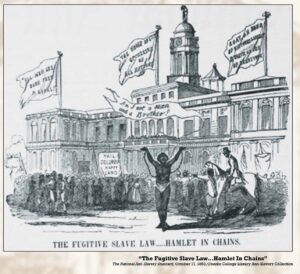

Immediately after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 passed, these jails saw a rise in captured runaways. This was evident in the story of James Hamlet, a formerly enslaved Baltimorean who became the first person to return to slavery because of the act. He successfully fled to New York in 1848, but shortly after the law passed, his former owner, Mary Brown, called for his arrest and return. He failed to win the case and returned to Baltimore, where Joseph Donovan held Hamlet in his private jail. Fortunately for Hamlet, abolitionists highlighted his story and accrued enough interest and money to purchase his freedom and return home.

While the fate of these two families from Staunton and Charleston remain unknown, they highlight people’s brave steps to flee through the train system and the continual fight for freedom after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.